By Isabel Hernández Gómez de Caso, CERL grantee 2023 to the Huntington Library, San Marino and Curator at the National Library of Spain, Madrid.

The CERL Internship and Placement Grant 2023 allowed me a unique opportunity to work with the Spanish incunabula collection at The Huntington Library in San Marino, California this past month of September. Under the supervision of Stephen Tabor, Curator of Rare Books, 33 new copies were added to MEI database. Also, 3 new owner records were created.

Established in 1919 by Henry E. Huntington, a distinguished entrepreneur and collector, The Huntington Library began as a private estate and later evolved into a center for art, literature, and botany. Featuring European and American masterpieces, the art collection coexists with an impressive 120-acre botanical garden of diverse plant species from around the globe. Its extensive library includes manuscripts, rare books, photographs, drawings, and all sorts of historical documents, focusing in different topics such as American History, British History, the Pacific Rim or the Hispanic History and Culture, among others.

The library houses a great compilation of over 5.200 incunabula, some of them so remarkable as one of the 12 surviving copies of the Gutenberg Bible printed on vellum. Other interesting copies include the first editions of Dante’s Commedia, the Cosmographia of Ptolemy and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales1. While the collection contains a large number of incunabula from across Europe, the Spanish prints stand out due to their rarity, a few of them are unique surviving copies.

Undergoing successive expansions and acquisitions, The Huntington Library continued to grow after the passing of Henry E. Huntington in 1927, adding new interesting pieces to its collections and broadening its educational and research initiatives. Among these initiatives, in the past years the Library has been studying the provenance of its collections and contributing with this information to MEI database.

Working with MEI database, one soon realises that the careful study of material evidence in a book not only unveils details about a specific copy but also illuminates its journey across continents, offering an insight into how the book market and the relationships between book collectors worked at a specific time; and therefore connecting libraries, sometimes even disappeared libraries, around the World.

One notable example illustrating this is the Huntington’s copy of Torquemada’s Expositio super toto psalterio by Paul Hurus and Johann Planck (GW M48227; ISTC it00528000; Huntington, 97498). This book, printed in Zaragoza, Spain, in 1482, and carefully studied by a contemporary hand, belonged later to the Italian nobleman Carlo Archinto (1669 – 1732), third Count of Tainate. Archinto was a man passionate about Arts and Architecture, strongly connected to the Spanish court of Philip V (1683 – 1746). He increased his father’s library, and we can still find his books marked with his personal arms in many Italian libraries. It looks like at some point this copy made its way from Italy to France since we find, together with Archinto’s, the distinct ex-libris of Henry Duhamel (1853 – 1917). Duhamel, an avid mountaineer and founder of France’s first ski club, possessed a noteworthy library that included not only contemporary works, but also rare books and incunabula. After his death, this library was dispersed in two sales in Lyon in 1921 and 1922.

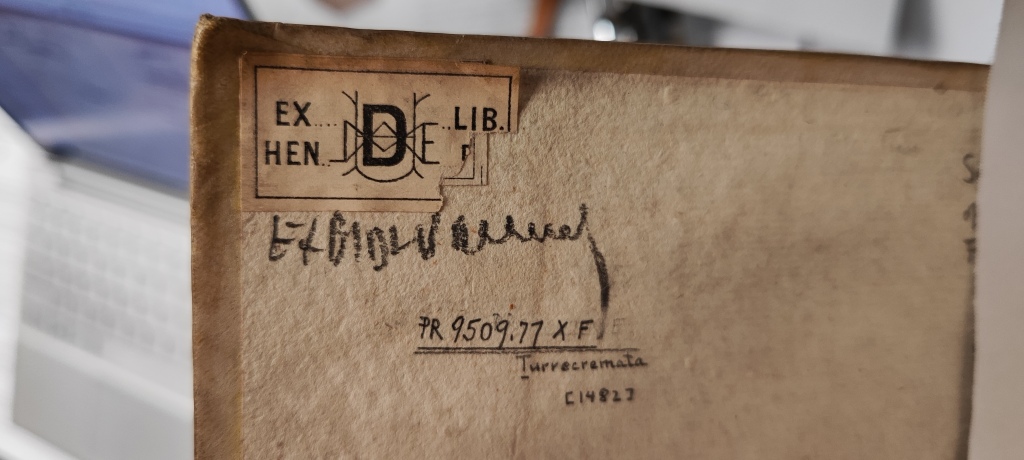

Carlo Archinto’s exlibris and Henry Duhamel exlibris, both in Huntington copy 97498.

It is likely that the German bookseller Otto Vollbehr (1869-1946) acquired this copy since he sold it to Henry Huntington in 1925, although we don’t know if there were any intermediaries. In fact, between 1924 and 1926, Huntington acquired a total of 2.385 volumes from Vollbehr. This is why many incunabula, especially those of Spanish or Portuguese origin, come from Vollbehr’s collection. However, the study of Vollbehr’s provenances remains waiting for a comprehensive study. In any case, although the story of this particular copy remains incomplete, it stands as a vivid example of how a close look can reveal previously unknown details about a book’s journey through time and across nations.

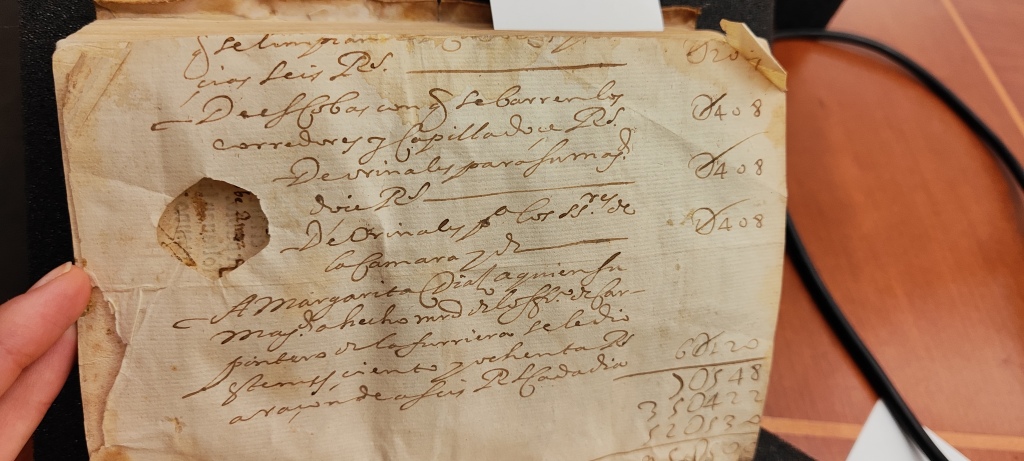

Another intriguing discovery that caught my attention was a copy of El libro del dialogo de sant Gregorio printed in Toulouse, but in Spanish, by Henricus Mayer, circa 1486 (GW 1413; ISTC ig00414000; Huntington, 87649). This copy contained numerous marginal notes by different hands; however, what was more fascinating was that the apparently plain parchment binding had, as back flyleaf, an accounting paper pertaining to the Spanish royal household. The accounting notes included the price of “chamber pots” for his Majesty and the payment of 6 reales per day to Margarita Díaz as “carpintero de la furriera”, that is, the employee in charge of maintaining the Monarch’s furniture. Thanks to our colleagues in the Archive of the Royal Palace in Madrid, we know that she was officially designated as such in 1633, which means that we can give an approximate date to the binding and to locate this copy in an establishment closed to or related to the Royal Palace.

Unfortunately, copy-specific information was not always relevant for 19th century collectors, who thought that bindings were expendable and had their books often rebound, their margins trimmed and their leaves washed or bleached. Despite these practices, they occasionally left behind beautiful examples of bibliophile’s bindings, which can also offer insights into a book’s provenance and significance. Victorio Arias (1856-1935) happened to be responsible for several of the Spanish-origin incunabula bindings in Henry E. Huntington’s collection. While some of his works were signed and others were not, his characteristic style, employing dark leathers and small blind and gold tools, allowed us to identify a few of his bindings that were lacking of authorship.

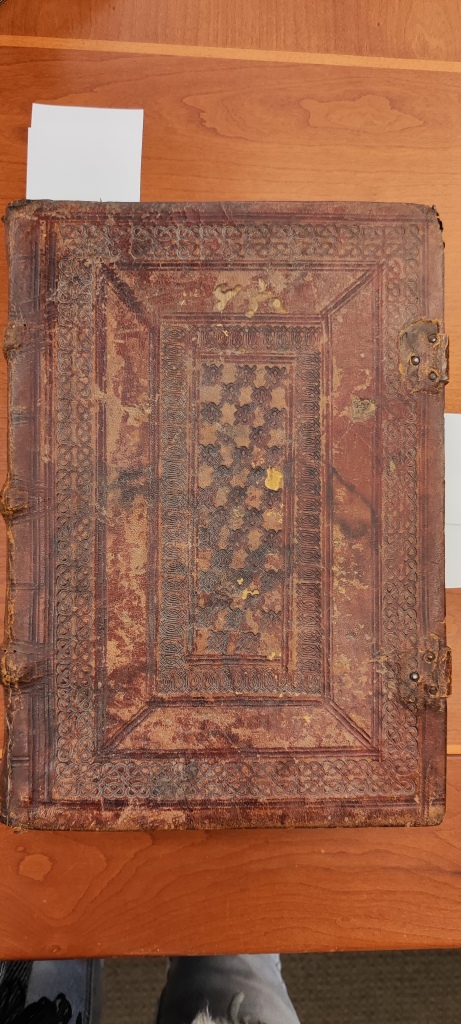

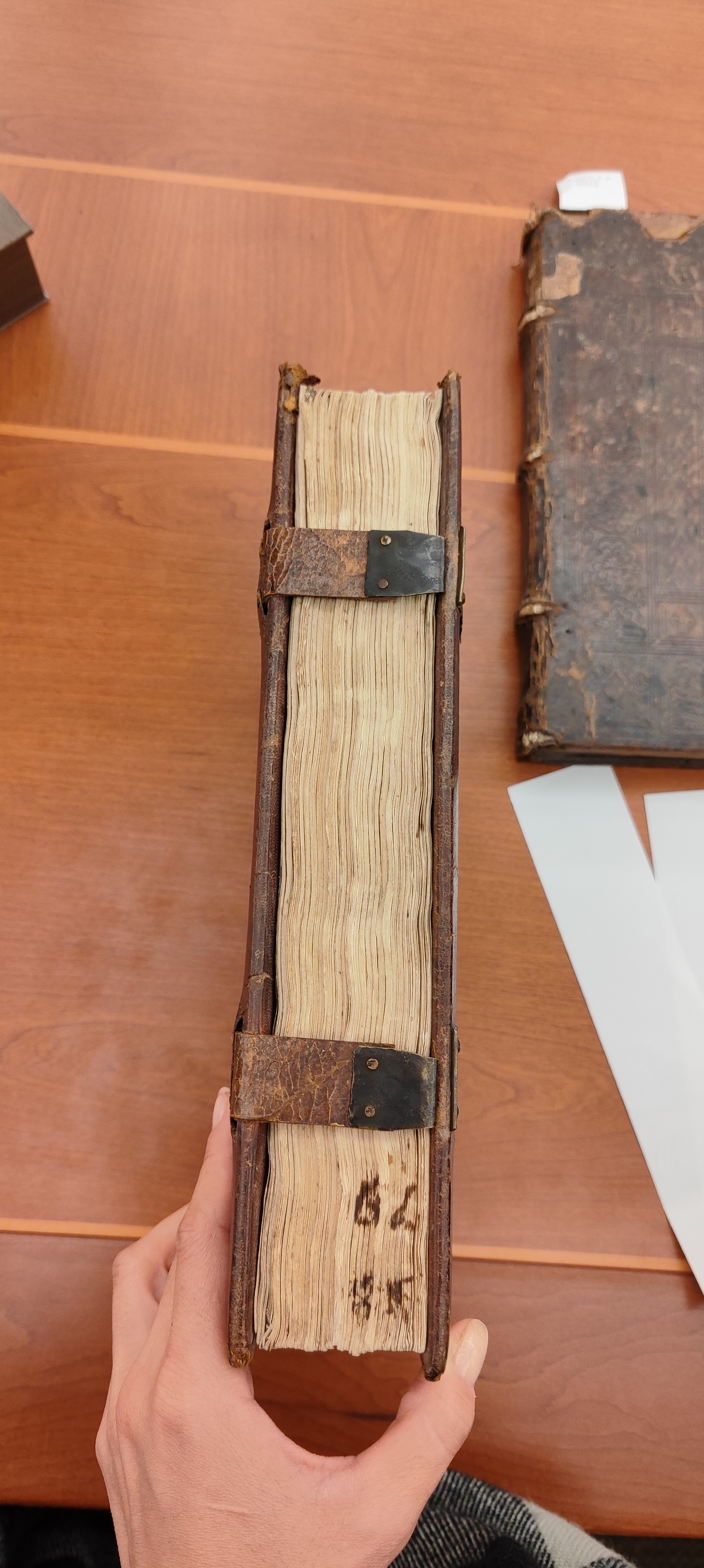

Some copies, however, have retained their original bindings, and among the Huntington’s collection we could find two examples of the genuine Spanish-Mudejar style. The Mudejar style has a strong Mediterranean influence in its decorations that reinterprets and merges Christian, Jewish, and particularly Islamic aesthetic traditions. This style was used widely not only in bindings but in all the decorative arts, and prevailed for centuries, from the Middle Age to the Renaissance. In bindings, it is characterized by the use of dark leathers, usually goatskin or calf, almost always over wooden boards, and small blind tools that gather in characteristic geometrical designs. Discovering these bindings within the Huntington’s incunabula was a true treasure.

A 16th-century mudejar binding using leather on wooden boards. The covers are blind-tooled, forming a geometric design with concentric frames and small rope interlaces. The spine is sewn on three double supports. In the fore-edge it has two metal clasps and a former manuscript unidentified shelfmark. (Petrus de Osoma, Commentaria in Ethicorum libros Aristotelis. Salamanca: [Printer of Nebrissensis, ‘Gramática’], 1496. GW M32642; ISTC io00115000; Huntington 93061)

As a librarian in the National Library of Spain, this experience has been very enriching for me. It has taught me where are my knowledge strengths and weaknesses. I have also learned valuable lessons on handling materials that often have much more than what we see at a first glance. Patience is essential when examining a book; one must look and look again until our eyes uncover the hidden aspects, until the book begins to speak. My experience at The Huntington Library will enable me to improve my MEI records in the National Library of Spain and to help my colleagues in the future when using MEI database.

On a personal note, I extend my sincerest gratitude to Stephen Tabor, whose great expertise, patience and generosity have made these four weeks a great time on both personal and professional levels; and to the wonderful people of The Huntington Library, who made me feel at home from the very first moment. Also, to my librarian colleagues in Spain and all the people responding in MEI’s editing list, that helped me to complete my records.

1The Huntington Library. Incunabula. Research Guide. 2023. Link: https://researchguides.huntington.org/incunabula [Consulted 10/11/2023]