By Agne Zemkajute, Book Museum exhibitions’ curator, and formerly curator of incunabula, at the Wroblewski Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences, Vilnius

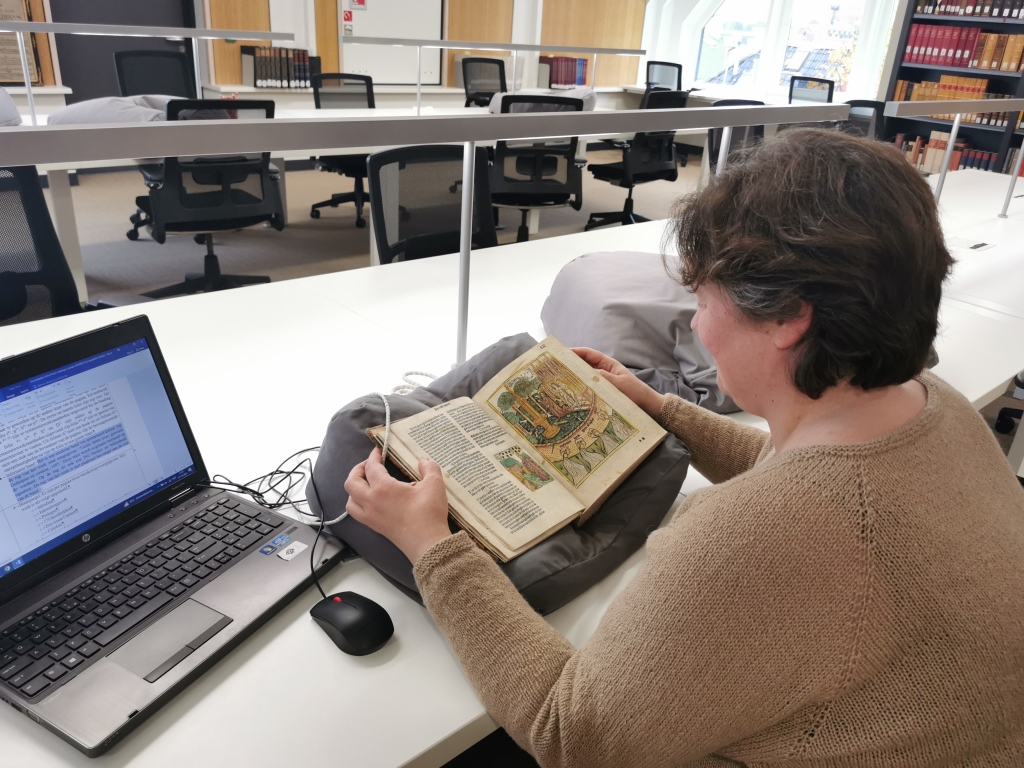

This October a CERL 2023 Internship Grant offered me the amazing opportunity to visit the University of Groningen Library and to spend four weeks in their Special Collections department. The main purpose of the stay was to research and catalogue the incunabula stored there in the MEI (Material Evidence in Incunabula) database. At the same time, it was a great opportunity to get to know this academic library, its work and daily routine.

The University of Groningen was founded in 1614 and is the second oldest institution of higher education in the Netherlands after Leiden, but the city has always been known as a center of science and scholarship. It is believed that as early as the 14th century there has been a school at the Martinikerk (St. Martin’s church). It was first mentioned in 1425. This school attracted not only local students, but also young people from neighboring countries. To this day, Groningen has remained a strong academic city, with a university ranked in the top 100 in the world, it is proud of its Nobel Prizes and other awards winners, and of Aletta Jacobs (1854-1929), the first woman in the Netherlands to receive a university degree.

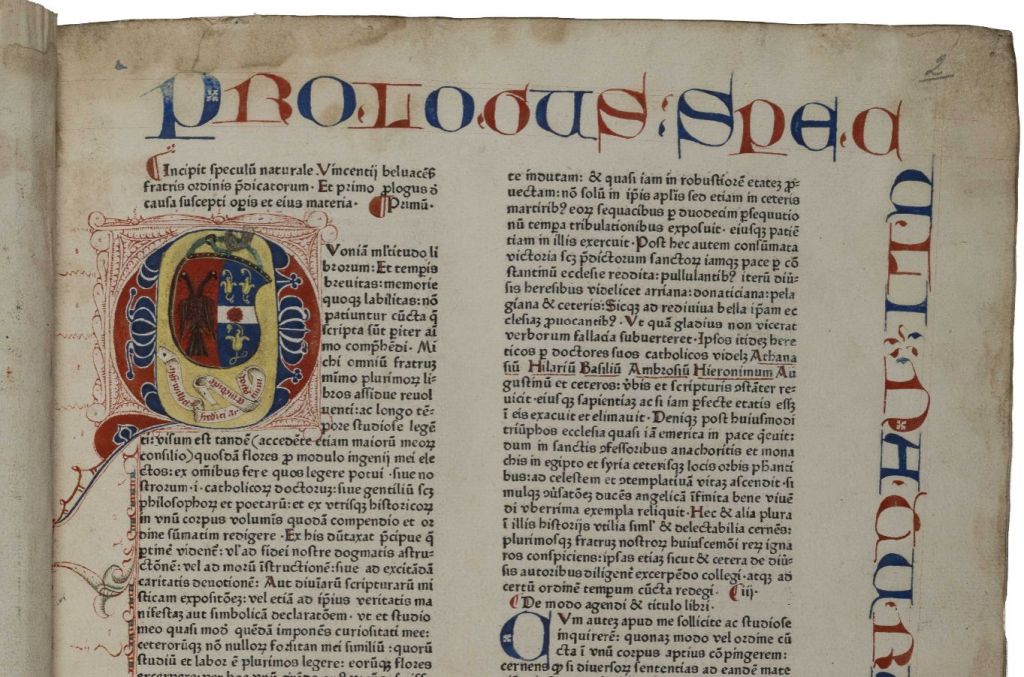

My research in the library, of course, was related to the early history of the city, and partly to its pre-university book heritage. There are over 200 incunabula, some of which came to the library shortly after the university was founded. As the name of the database on which I have based my research – Material Evidence in Incunabula – suggests, its focus is not on the author of the book, the content, and often not on the printer, but on the identified and unidentified owners, readers, commentators, and the authors of the more or less elaborate drawings in the books. Having worked mainly with incunabula preserved in Lithuania so far, it seemed incredible at first how a book could have been brought to Groningen as early as the end of the 15th century, bound there, changed hands two or three times, and all this movement could have taken place within a relatively small area. Indeed the entire physical journey of the book over more than 500 years often rested within this area. The incunabula in Lithuania which I was familiar with travelled more, were influenced by political events, and very often the books were forced to change their places and owners. In Groningen, I worked with some books which once belonged to the priests of the Martinikerk (1). One of them, Wilhelmus Frederici (before 1452-1525), had at least 14 incunabula (2).

He left the books he owned to the library of the church where he served. Some of the books have inscriptions by Frederici himself.

He mentions when he bought incunabula and how much he paid for them, a few books he inherited from Johannes Frederici (3), who died in 1484 (possibly his father or brother; the exact relationship is unclear). Other books have later entries made by the librarian of the Martinikerk, who mentioned the benefactors in the inscriptions. Modern book researchers can be very pleased to find such identification notes of the previous owners of a particular book, which allows a longer history of the book to be traced. This was certainly not the intention of those who recorded this information. Their entries were an invitation to a reader to remember in prayer the benefactors who made it possible for them to read these books (4).

Groningen officially adopted the Reformed faith in 1594. Many of the books from the closed Catholic institutions ended up in the library of the Martinikerk which was the principal church of the city. In 1622 the City Council allowed to transfer these books to the University Library which had been founded in 1615 just a few hundred metres from the church, and almost all of them have been preserved here to this day. No list of these books survives so provenance research helps to identify them. It is not known exactly where the church stored its library’s books, so one can only look at the church building and speculate as to where this might have been. During my research time this church was closed for visitors. However, on the evening of the last day of my work at the library I managed to get inside the church in a not-so-legal way – there was a rehearsal going on at the time and someone had forgotten to lock the door, so I managed to see almost the whole church. After all the research done, I couldn’t not visit such an important place for incunabula!

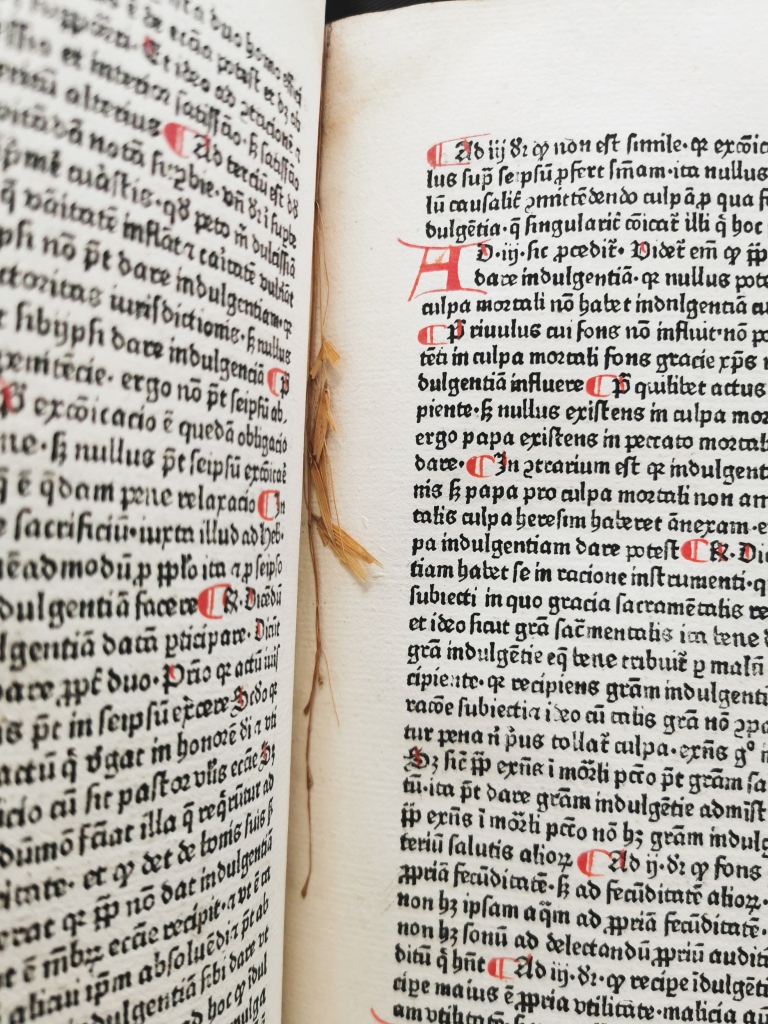

Sometimes the most interesting things are not the ones that we are normally looking for. It is great to be able to tell the story of the book, but sometimes it is even better to find something strange or curious. Why, for example, one page in the middle of the book was left not rubricated? (5) The rubricator somehow missed this page? Maybe… But what about the book that is missing rubrications in some leaves, some pages and a quarter of one page?(6) If this had concerned half of an incunable, maybe we could guess that the owner of the book became short of the money? But such pages can be found throughout the entire book. Another book was missing a sheet (leaves 2 and 7) and another had the text copied on parchment (7). Maybe this was done by the book’s owner Wilhelmus Frederici himself? We will never know why some pages were not rubricated or two leaves were missing, but it was very interesting to discuss such curiosities with the colleagues and to create hypotheses, some of them less probable than others, but all theoretically possible.

We can try to speculate on the causes of the above-mentioned curiosities. But some of the other finds are just interesting finds or… the possible beginning of a story. Why did someone use a stalk of grass as a bookmark? (8) It is, after all, very thin and fragile, certainly not the kind of thing that can last for long. But safely hidden among the leaves, it survived a long time. Insects in books always make me curious. What are they doing inside the books? This time it was a poor spider at the bottom of the page. (9) Did someone accidentally crush it when the book was closed? Or was someone very afraid of spiders and we discovered the crime? Someone killed the spider? It’s fun to discuss such findings with the children who visit the library. They can easily come up with more than one or two explanations for such findings. But could this also be the beginning of a detective novel yet to be written? Maybe the spider was killed for a reason, and the blade of grass was a significant means of transmitting information… After all, we do not have to be serious in our researches all the time? Or do we?

Another curious find that is related to the history of book writing was one endleaf made of reused parchment with a Missal text which was written at the end of the 15th century. This leaf of parchment had never been bound in a book and had never been used in liturgy. This leaf has only the main text written in black ink, but there are no rubrics, so for some reason the leaf remained incomplete. (10) Colleagues in Groningen were glad of this find, because for them this will be a great example of the process of rewriting a manuscript book. And I thought how lovely it would be to have something similar in our collections. What a great example this could be for teaching, lectures, etc. At least I know where to find its digital copy (the library has already digitized its incunabula).

These are just a few examples of the many interesting and useful things that I learned during this month. Some of the information was revealed by the incunabula themselves, other I discovered in the modern books that I found here. And, of course, I was learning from the colleagues that I met in Groningen. After all, our knowledge is based not only on the literature we read, but also on our experience with the books we work with. Different historical and cultural contexts also shape different social attitudes towards books, different reading traditions and different histories of books themselves. All of this gave me a lot of ideas, which, I believe, in time will get more concrete forms of expression and become part of my future projects, exhibitions or teaching.

I am very grateful to CERL and the University of Groningen Library for the possibility to come and learn more about this collection. I’m even a little bit jealous of those who will finish cataloguing these incunabula in MEI and who will be able to see them as a full collection and not as a part.

(1) Martinikerk in MEI: https://data.cerl.org/owners/00029611

(2) Wilhelmus Frederici in MEI: https://data.cerl.org/owners/00021440

Book with coat of arms of Wilhelmus Frederici: Vincentius Bellovacensis, Speculum naturale. [Strasbourg: The R-Printer (Adolf Rusch), not after 15 June 1476]. Folio. GW M50635; ISTC iv00292000; Groningen UL: uklu INC 189 (1); https://data.cerl.org/mei/02140528

https://facsimile.ub.rug.nl/digital/collection/incunabelen/id/54665/rec/1

(3) Johannes Frederici in MEI: https://data.cerl.org/owners/00029609

(4) Wilhelmus Frederici invites to pray for Johannes Frederici (‘Ex Testame[n]to m[a]g[ist]ri Joh[ann]is fride[r]ici i[n] Zeeripis Utentes orent p[ro] eo’; fol. 1r), in Antoninus Florentinus, Summa theologica. Venice: Leonardus Wild [and Reynaldus de Novimagio], 1480-81. Folio. GW 2187; ISTC ia00873000; Groningen UL: uklu INC 18 (4); https://data.cerl.org/mei/02149964

https://facsimile.ub.rug.nl/digital/collection/incunabelen/id/38407/rec/1

Martinikerk library’s librarian (?) invites to pray for Wilhelmus Frederici (‘Ex Testamento Wilhelmi friderici Utentes orent p[ro] eo et suis benefacto[r]ibus’, fol. 1 v), in Avicenna, Canon medicinae. [Strasbourg: The R-Printer (Adolf Rusch), after Feb. 1473]. Folio. GW 3114; ISTC ia01417700; Groningen UL: uklu INC 34 (2); https://data.cerl.org/mei/02139957

https://facsimile.ub.rug.nl/digital/collection/incunabelen/id/56192/rec/1

(5) One non-rubricated page (p5 v), in Johannes Beckenhaub, Tabula super libros sententiarum Petri Lombardi cum Bonaventura. [Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, not after 1494]. Folio. GW M32527; ISTC ib00292000; Groningen UL: uklu INC 52 (2.2); https://data.cerl.org/mei/02150280

https://facsimile.ub.rug.nl/digital/collection/incunabelen/id/50323/rec/1

(6) Partly rubricated book, Johannes de Bromyard, Summa praedicantium. [Basel: Johann Amerbach, not after 1484]. Folio. GW M13114; ISTC ij00260000; Groningen UL: uklu INC 56; https://data.cerl.org/mei/02140258

https://facsimile.ub.rug.nl/digital/collection/incunabelen/id/51865/rec/2

(7) Book with leaves H2 and H7 missing, in Johannes Gerson, Opera, etc. [Cologne]: Johann Koelhoff, the Elder, 1483-84. Folio. GW 10713; ISTC ig00185000; Groningen UL: uklu INC 90 (4); https://data.cerl.org/mei/02150005

H1v-H2r: https://facsimile.ub.rug.nl/digital/collection/incunabelen/id/27351/rec/100

H2v-H3r: https://facsimile.ub.rug.nl/digital/collection/incunabelen/id/27352/rec/100

H6v-H7r: https://facsimile.ub.rug.nl/digital/collection/incunabelen/id/27356/rec/100

H7v-H8r: https://facsimile.ub.rug.nl/digital/collection/incunabelen/id/27357/rec/100

(8) Very fragile bookmark (?) – A stalk of grass, in Augustinus de Ancona, Summa de potestate ecclesiastica. Cologne: Arnold Ther Hoernen, 26 Jan. 1475. GW 3051; ISTC ia01364000; Groningen UL: uklu INC 14; https://data.cerl.org/mei/02149944

https://facsimile.ub.rug.nl/digital/collection/incunabelen/id/12640/rec/184

(9) Spider at the bottom of the text (146 r), in Articella. Venice: Baptista de Tortis, 20 Aug. 1487. Folio. GW 2680; ISTC ia01144000; Groningen UL: uklu INC 27; https://data.cerl.org/mei/02149997

https://facsimile.ub.rug.nl/digital/collection/incunabelen/id/35353/rec/1

(10) Non-rubricated parchment endpapers, in Antoninus Florentinus, Summa theologica (Partes I-IV). Venice: Leonardus Wild [and Reynaldus de Novimagio], 1480-81. Folio. GW 2187; ISTC ia00873000; Groningen UL: uklu INC 18 (4); https://data.cerl.org/mei/02149964

https://facsimile.ub.rug.nl/digital/collection/incunabelen/id/38406/rec/1